I remember being a kid in the 1960s and 70s. The world was an endless summer, and a lot of my memories involved running around on lawns. Mostly, of course, under sprinklers.

But another thing that I remember about those lawns is that they could get prickly. Seriously prickly. It got to the point where I was afraid to cross certain areas without shoes because of the murderous things that would stick in your feet.

They were stealthy little bastards, too. I don’t remember ever being able to tell which part of the lawn was affected. Visiting a friend’s place was especially risky. You’d gird your loins, take your life into your hands, put your feet on the line, and find where the prickles were.

The dreaded Bindii

The prickles in my lawn were called Bindii, Bindi-eye, or Soliva Pterosperma if you’re interested. Incidentally, I think pterosperma means “seeds with fingers”, and the photo shows how apt that name is.

There are two reasons why I was never able to see Bindii (apart from not knowing what to look for).

First, they’re green (of course) but they also look soft, with fluffy little leaves. They’re not all that different to a small version of Parsley. Very innocuous.

But the second reason is that the seeds only become really hazardous after the plant itself (an annual) has died off. The seeds themselves are spoon-shaped things that grow in nodes resembling tiny artichokes, all clustered into a ball. Each seed has a vicious spike that points upward.

It’s all about colonisation

The plant’s strategy for spreading is that after it’s dried out, the seed ball disintegrates when touched. The unwilling barefoot collaborator steps on the seed, impaling themselves on the spike. The victim lifts the seed and carries it away a few paces before falling to the ground in agony and extracting it. Where the seed is discarded, a new plant will take root.

So… the photo

I’d found a few of these things in my own yard and decided to investigate.

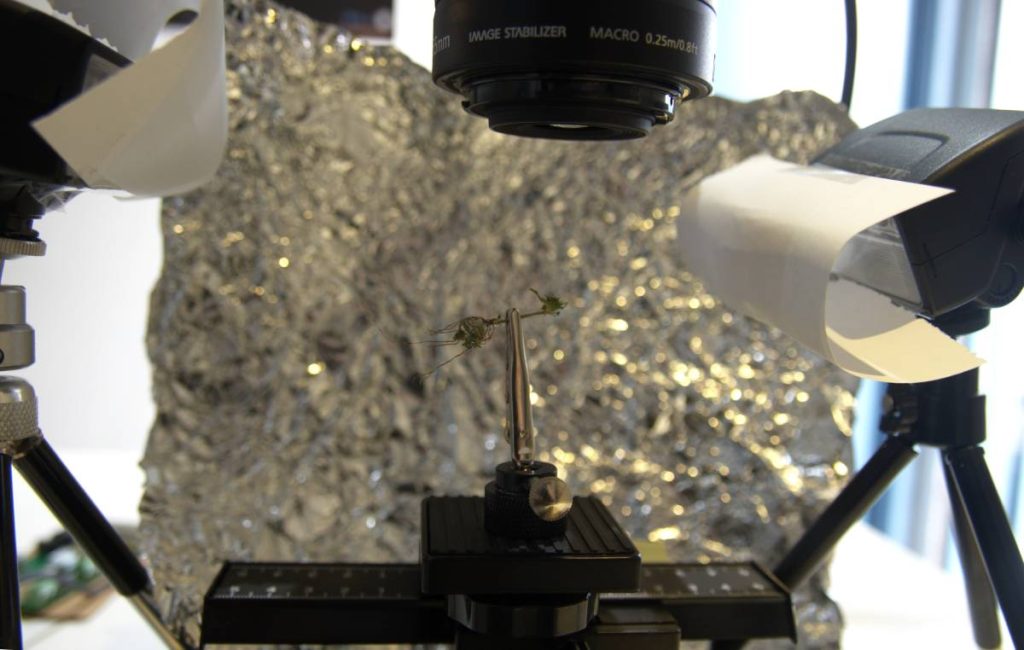

At some cost to my fingers, I pulled this Bindii out of my lawn and photographed the seed ball using the WeMacro Rail and a reversed lens. The node I’m imaging is the one on the right, directly under the lens.

You can see how much effort I took to get nice diffuse light from my two flashes. There are pieces of white paper about an inch or so in front of each flash. These flashes also point mostly towards the back wall of the little studio, which is a sheet of wrinkled aluminium foil. (I moved them for the glamour shot). The idea was that at the moment the flashes went off, they would bathe the Bindii in light from as many directions as possible. This prevents the harsh shadowing that flashes can cast. I took the image from above, and there is a black background, well out of focus beneath.

Having a reversed lens gives the photo an infinitesimal depth of focus. Each image is a mess of blurry colour, with just a few areas having sharp focus. Normally this is a horrible problem, and this is where the WeMacro Rail comes to the rescue. It fires the camera, moves downward slightly, then fires again, repeating this until the focal plane has moved all the way through the subject. I never have to touch the studio to refocus, because the smallest movement will ruin the shot. I’m not normally even in the same room, because my phone controls the WeMacro via Bluetooth.

Processing

After I get the subexposures, the focus stacking software takes over. I use Helicon Focus, which identifies all the focused areas and pieces them together like a jigsaw puzzle. I can select parts if I don’t like what Helicon has chosen (who am I kidding?), and finally I finish off in Photoshop, normally for saturation and perhaps a slight high-pass filter.

This image is made up of 41 subexposures all taken at different distances from the plant, before being taken apart and re-integrated using Helicon Focus.

A fearsome creature, don’t you agree?