A plant that eats animals

Drosera capensis is an insectivorous plant native to South Africa. Sundews thrive in low-nutrient soil because they’re able to gather their nutrients from “other sources” (mwa ha ha!). Because other species do poorly in these areas, Sundews have an advantage.

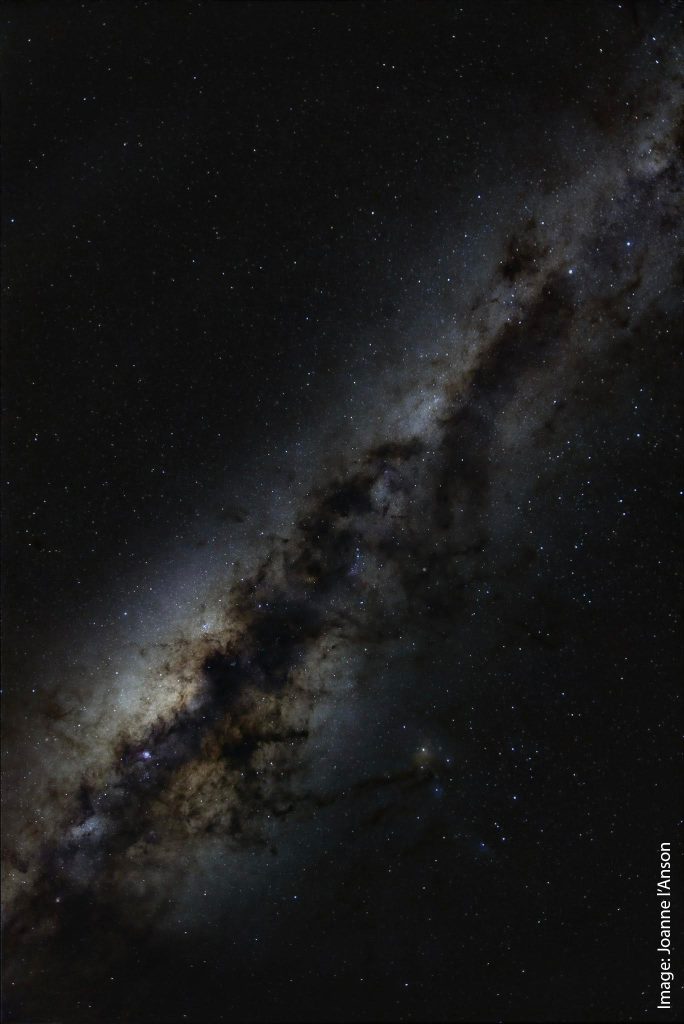

D. capensis is similar to the native Sundew species we find in Central Victoria. Some of the astrophotographers at the ASV see them a lot, although they may now know it. At some times of the year Australian Sundews are thick on the ground at the ASV’s dark sky site. If only the astronomers looked down, rather than up!

Paul’s wife Lynn lent us a Sundew for our macrophotography, and this one had already claimed a few victims. We set it up and took a series of test stacks.

The setup

The WeMacro was a great help, automating the whole capture process. The lens was a plain 200mm prime, focused at infinity. On the filter thread of the lens we placed the relevant WeMacro adapter, a 42mm RMS adapter, and then an infinity microscope lens.

This arrangement means that between the microscope lens and the front element of the camera the light from the subject is parallel, meaning you can do useful things like insert filters, irises, etc.

Incidentally, the RMS thread is a very old standard, decided by the Royal Microscopy Society around 1858. It’s a Whitworth-profile thread of 0.8 inches diameter and a pitch of 36 turns per inch. Other threads are used in microscopy, but the RMS is the most common standard, even after 166 years.

Challenges for the shoot

You can see from this phone image that the Sundew has long, strap-like fronds. These gave us a few problems because they tended to shake around when the WeMacro’s stepper motor moved. Using the WeMacro’s interface, we were able to pause before firing the camera, giving it time to stop. The Canon’s shutter didn’t help – a mirrorless DSLR would have been handy.

Helicon Focus also had a few problems choosing the focus points for stalks that were in front of the leaf. The focus stacking process looks through each one of the dozens of frames taken by camera, and chooses which has the best focus, before arranging all these pixels jigsaw-like into the final image.

Helicon Focus also allows you to manually override this and choose which frame would contribute to the final image. This gave us an image we considered to be good enough.

The final result

The image itself is fairly gruesome. D. capensis is covered with long flexible stalks, each of which is tipped with sticky goo (I think that’s the scientific term). In this particular case, some unfortunate insect (she’s about 1mm in length) has come to investigate and become trapped.

Over time, enzymes in the plant will digest the insect, and the plant absorbs the nutrients. Larger insects tend to struggle more, leading to the frond wrapping itself around the insect.

Ughh!

Some of the Wemacro products available from Sidereal Trading.

-

Wemacro Fine X-Y adjustment platform 2.0

$169.00 Add to cart -

WeMacro Focus Stacking Rail (100mm) with Power Bank Cable

$745.00 Add to cart -

Wemacro GFX mount Lens Tube

$369.00 Add to cart -

Wemacro GFX mount Raynox DCR 150 tube with Raynox Lens

$535.00 Backorder Now -

Wemacro MicroMate

$519.00 Backorder Now -

Wemacro Raynox DCR 150 Tube Lens (Pro)

$325.00 – $485.00 Backorder Now This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Wemacro Rotation stage with specimen holder

$169.00 Add to cart -

Wemacro Vertical / Horizontal Stand

$59.00 – $335.00 Backorder Now This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Wemacro XYR Stage with Specimen Holder

$329.00 Backorder Now